Marae Moana Act just the first step

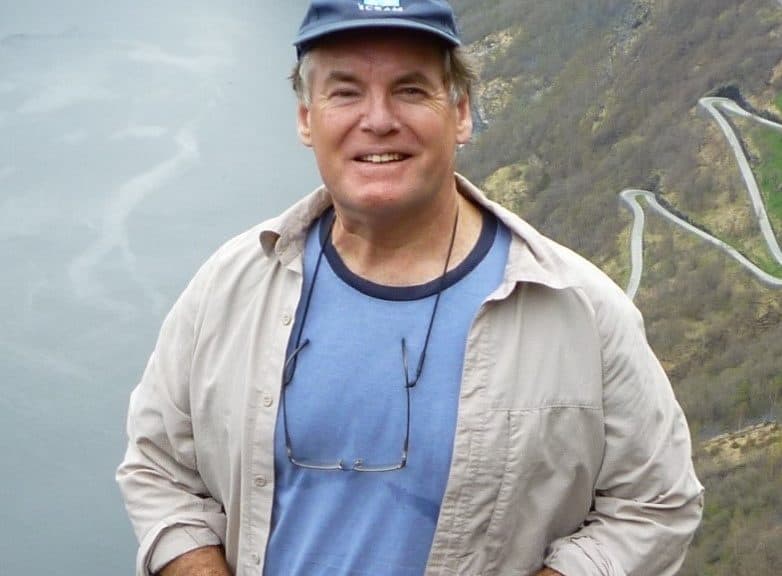

Jon Day, previously one of the directors with the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA) —the agency tasked with overseeing the grandfather of modern marine-protected areas (MPAs)—says that while passing the Marae Moana Act is an important step on the journey to responsible ocean management, it is just the first of many steps.

“Oceans are a vitally important part of how the health of the world continues, especially as oceans cover over 70 per cent of the surface of our planet,” Day says. “Large MPAs can play an important role in the conservation of these areas. But just because you set aside a large area for conservation doesn’t necessarily mean it’s going to be well-managed.” In other words, closing the gap between intention and action takes a lot of work.

Day became involved with the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (GBRMP) in 1986, a decade after the Australian Parliament passed the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Act. In 1975 when the Act was proclaimed, time was of the essence because mining and drilling projects were being proposed and the public was concerned.

Initially, the Act did little more than set an outer boundary within which a marine park could be declared; it would be 13 more years before the park was spatially managed, or zoned. Similar to Marae Moana, the GBRMP is a multiple-use MPA, meaning various activities, including different types of fishing, are allowed in various zones.

Before the Cook Islands passed the Marae Moana Act, Day advised Jacqui Evans, now the director of Marae Moana, that the best course of action would be to “just start somewhere”. He explained that though every place is different, in his experience the process of zoning a large area of ocean took years, was controversial, and depended on genuine engagement with the community.

“We zoned the GBR Marine Park in stages over many years,” Day recalls. “We didn’t do it all up front. We zoned just a small part and learnt lessons and then zoned another. … When I spent time with Jacqui in the Cook Islands, I suggested they might try to set the park up in stages. [I said] follow the Great Barrier Reef model—put in place an outer boundary with a long-term vision and then spend time working with the community, bringing them along on the journey.”

Day has documented the lessons he learnt working with the community. In 2017, he published a paper in the journal Coastal Management identifying 25 ways park managers can truly engage. In the paper, Day describes the tools that were useful in the Great Barrier Reef zoning process, including a simplified fact sheet written in layman’s terms and devoid of terms like “biodiversity”, telephone polls to find out what “the silent majority” was thinking, a visually appealing brochure, and making maps and zone coordinates widely available.

Among the most effective tools were the well-advertised community information sessions held at various locations, during which planners and park managers would be stationed at a school or another public place between 3pm and 7pm, available to answer questions.

As a result of these tools, public participation led to “ huge changes during the planning process”, according to Day’s paper. In the end, park managers took into account the best available science as well as more than 31,000 public submissions.

Even now, decades after being zoned, the GBRMPA continues to face some opposition. Day says park management is often about compromise.

“Fishers and environmentalists both have a legitimate interest in the resources within an area,” he says. “The best method is to ensure that both can co-exist while minimising the impacts on the other. You’re rarely going to have a win-win for everyone. It sounds lovely but it’s almost impossible. You have to aim for the best possible compromises.” He adds that once a marine park is zoned, it must be continually and carefully managed.

“Information changes, the distributions of species change, threats change and social attitudes also change… so you have to periodically adapt management and update the way you interact with people,” he says. “Today we recognise that some of the measures we put in place years ago were no longer adequate. The ocean is a huge, fluid, interconnected ecosystem. It changes daily with the tides but also with the seasons and with climate change so there is a need to continually review management to see what’s working and what needs to be improved.”

The Marae Moana Technical Advisory Group has been tasked with preparing procedural regulations for the spatial planning of Marae Moana; this will represent the next major phase of planning the Cook Islands’ multi-use marine park.

“Based on the GBRMP model, we can see that it takes years to develop a good marine spatial plan that is accepted by most,” says Evans, who is working with a committee to determine the most effective and sustainable financing mechanisms for Marae Moana. “We’re aiming to do ours by 2020. This is a very ambitious deadline because a lot of our marine space is deep ocean and it’s very expensive to collect deep ocean data.”

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration of the U.S. government has offered financial support for this work. Further support could come from NIWA, New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, Evans says. The Seabed Minerals Authority will be contributing any data collected by companies who procure a licence to explore the Cook Islands’ seabed. –Release