Aronga Mana using influence for conservation

What the aronga mana lacks in political power, it makes up for in influence and resolve.

Public service is a responsibility the formal bodies of traditional leaders—the House of Ariki, occupied by 26 high chiefs, and the Koutu Nui, comprising more than 800 sub-chiefs—take seriously.

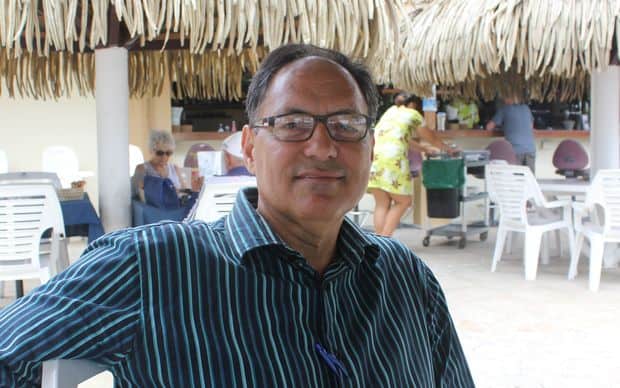

“The difference between the traditional leaders and those in power is they’ve got authority to do things—resources, budget, all kinds of things we don’t,” says Paul Allsworth, president of the Koutu Nui. “But that doesn’t mean we don’t make our voices heard.”

Allsworth explains that the executive committee of his organisation meets monthly to discuss a range of matters—land tenure, immigration laws, the number of vehicles on the roads, a ban on plastic bags, and the ever-topical marine environment. This last issue is one to which the Koutu Nui has demonstrated particular commitment.

“We’ve got strong views,” Allsworth says. “We are pro-conservation and believe in environmental protection first and foremost.”

Allsworth recalls the traditional leaders who protested, publicly, the signing of new contracts with purse seiners in 2015 and 2016.

“We marched against it and we’re still against it,” he says. “We’d rather keep our fish for our people than sell it. That is a clear point of view that has come through.”

The Koutu Nui also took a strong position on Marae Moana, the Cook Islands’ marine park. Traditional leaders supported the creation of exclusion zones, which now encircle all islands in the Cook Islands and ban large-scale fishing and mining within 50 nautical miles of any shore. They wanted 100 nautical miles but compromised and settled for half that.

Allsworth describes Marae Moana as “an extension of the rā’ui”, a modern tool that hedges against modern pressures but is rooted in the same values that underpin traditional systems of resource management. He wonders, at least in this interim stage before the marine park is fully zoned and implemented—before the gap between law and action is closed—whether conservation, seabed mining, and purse seining can coexist.

He’s encouraged, though, by the fact that the aronga mana is represented on the Technical Advisory Group set up to advise the Marae Moana Council, which in turn manages the Marae Moana policy.

“Unfortunately, some bureaucrats neglect, for one reason or another, the inclusion of aronga mana in all activities of the community,” he explains. “The aronga mana is a fabric of our society linked to every individual. Every Cook Islander comes from a tribe. Every MP [Member of Parliament] comes from a tribe. Cabinet ministers come from tribes… If you understand that concept then you know we’ve got such close connections we should work together for the same objectives.”

Management of the environment is an area in which he believes political leadership consistently overpowers traditional leadership.

“You take up this role to protect and look after the interests of your tribe,” he says. “You do it on behalf of the people and the people are the ones that come from your tribe. That’s something the aronga mana want to instill into our community. Once everyone fully understands that, then things will change.”