Marae Moana Still A Step Ahead

At the UN General Assembly meeting recently the United Kingdom’s government challenged the world to protect 30 per cent of all oceans before 2030. “It took my breath away,” said Lewis Pugh, a British maritime lawyer who once swam for 49 days to protest the way the world is treating the oceans. The call to action was significant because currently, according to the Atlas of Marine Protection, less than four per cent of the world’s oceans are conserved.

The UN offers different data—seven per cent, because it publishes what it receives from countries. There are disputes, however, about how much of this area is actually and effectively protected. Whichever figure is accurate, still it represents a speck on the larger canvas. The ocean covers roughly 70 per cent of the planet. About 60 per cent of it belongs, officially, to no-one. This area is known as the high seas, and according to the World Database on Protected Areas, just one per cent of it is protected.

The United Nations has set a target of conserving 10 per cent of the world’s oceans by 2020. People who have attended regional or international meetings, who know the difficulty of reaching consensus in a room full of political and commercial interests, call this goal ambitious. They know that opposition to marine conservation is rife. Marine data scientists from National Geographic’s Pristine Seas project found this year that more than half the world’s oceans are being industrially fished, and new technologies are increasing demand for minerals on the seafloor.

Calling for 30 per cent protection, then, is fraught. University of York scientists recently concluded, after reviewing more than 100 studies, that it’s also necessary. “There’s been huge interest and controversy over how much of the sea we really need to protect in order to safeguard life there and the benefits it provides to humanity,” Professor Callum Roberts was quoted as saying. “The science says we should raise our ambitions and protect something of the range of 30 to 40 per cent of the oceans from exploitation and harm.”

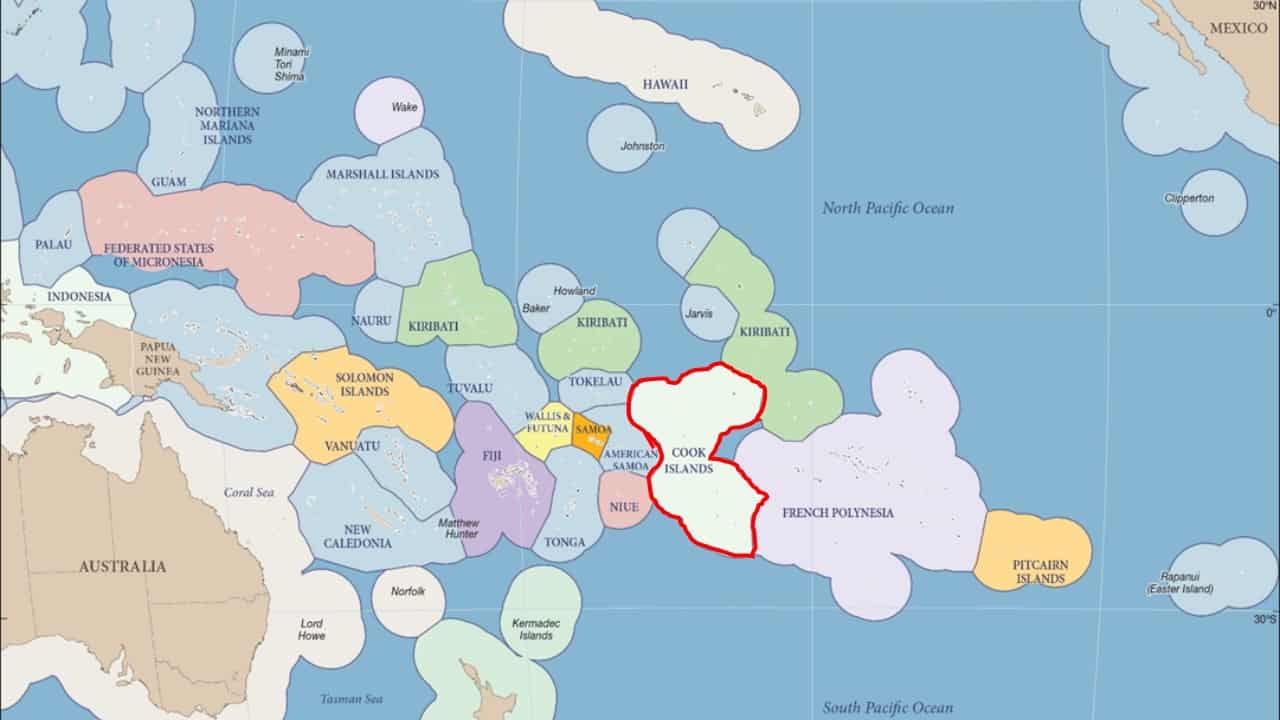

The Cook Islands has already raised its ambitions; Marae Moana remains the world’s largest marine protected area. Kevin Iro, who conceived of the idea years ago, has hopes it will create a ripple effect throughout the region. “From my perspective and from the prime minister’s perspective, what we’re trying to establish is a complete paradigm shift in how we, as Pacific peoples, view the ocean,” he said. “We’re all using this western construct that says let’s save 10 per cent by 2020 or 30% by 2030. We’re thinking the opposite.”

What he means by this is he’s thinking about pockets of industry in a patchwork of protection, not the other way around. This perspective informed the name of the Cook Islands’ marine protected area—Marae Moana, the sacred ocean, because the ocean is not just a site for doing business. In other words, protection is the rule, not the exception. “We go out to these international meetings and express this and people have this stunned-mullet look on their faces,” Iro said. “We’ve been brainwashed into thinking we have to just put aside these little areas and that’s obviously not working.” As the Cook Islands government expedites discussions with mining companies, Marae Moana assumes new significance.

For Iro, it remains a message to the region, and world, that marine protection is possible and necessary. “We have the ability to actually make a stand together,” he said of Oceania. In the Pacific, there are more Exclusive Economic Zones, or EEZs—ocean spaces extending 370 kilometres or less from a country’s coastlines—than in any other ocean. The marine area over which Pacific nations have jurisdiction is vast. “Year after year, fish stocks decline and pollution gets worse because we haven’t really, as a Pacific people, taken ownership of our oceans,” Iro said. “Our ancestors revered the ocean.

They thought if they didn’t do well by their lagoon, the god of the sea would punish them. I’m not saying we revert back to that. “I’m saying that spirit—that holistic view of the ocean—comes when Pacific people take ownership of the ocean beyond what they can see. That’s the movement I think we are creating.”